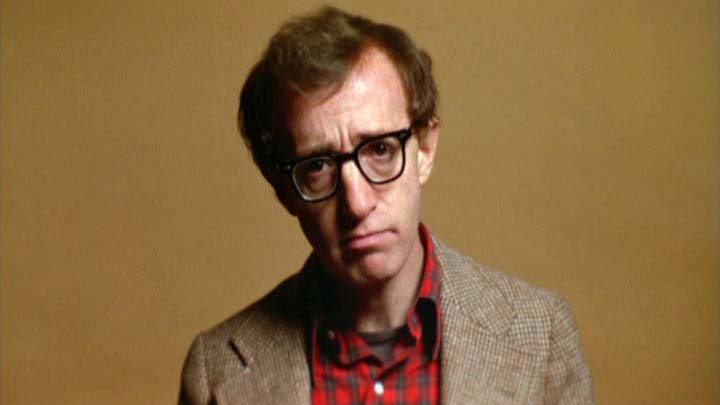

What does it mean when one of your favorite public figures becomes problematic? This was a question I asked myself on Sunday night, after reading Dylan Farrow’s open letter on Nick Kristoff’s blog. The letter, which most of the Internet has at least some familiarity with at this point, begins and ends by asking the reader what their favorite Woody Allen movie is, while the letter itself details the abuse Allen was first accused of committing in the 1990s. The allegations aren’t new, having first made the media rounds in 1992 during the vicious custody battle between Allen and Mia Farrow. The most pronounced and possibly impactful difference this time is that Dylan, now 28, can speak for herself. Her letter has clearly struck a chord with many who feel she never received justice due to Allen’s status in film, as well as those who look at her letter as a brave example of a victim refusing to be silenced.

There are plenty of pieces floating around the internet that dissect the 1992 investigations that followed the Farrows’ original accusations of abuse. There are also plenty of pieces that rip to shreds any possible evidence that the abuse may not have taken place. That kind of back and forth is to be expected when a 20-year-old scandal is back in the limelight. But there’s also a disquieting angle being taken by many. The Internet is locked in a righteous battle at the moment, and unless one is willing to take sides, they are complicit in the sexual abuse of children and the societal structuring that allows that abuse to continue. This is an angle taken up by Dylan herself, when she called out not only the actors and actresses that work with Allen but also fans, daring them to still have a favorite Woody Allen movie at the end of her letter.

Let’s try and remove ourselves from the immediate emotional tug of this situation, and consider the implications of this line of thinking. Is it the responsibility of every person to place personal sanctions on those who engage in behavior we don’t agree with? In an ideal world, perhaps. But in practice it’s far more complicated. Although I know and understand the toll of factory farming, I continue to buy meat at the store. Despite believing strongly in worker protections, I buy clothes from places like H&M. I’m opposed to common banking practices, but I still use banks. I don’t condone adultery, but I was just as swept up in the idea of Ronan Farrow being Frank Sinatra’s son as the next person.

Are these things mutually exclusive? Or is there some sort of karmic cycle by which one is able to absolve these discrepancies?

When I started really thinking about Woody Allen and his work, I found the idea of foreswearing my years of being a fan very difficult. On one hand, it’s hard not to be swept up in the angry mob. On the other, I’m still the same person who laughed out loud in public reading Allen’s writing or who cries every time I watch “Annie Hall.” Could I continue supporting survivors of abuse and remain a fan of Allen’s work?

My first thought, interestingly, was Bing Crosby. Crooner, actor, and child abuser. I don’t change the radio station when Crosby comes on or seethe with rage when one of his movies is played. I’m well aware of the fact that he beat his children, but I don’t consider my singing along with his Christmas album as shrugging that side of him off or supporting it. Society continues to celebrate Crosby and his work although the abuse is a well known and oft repeated part of his legacy. Is there more disconnect between the wholesome image of Bing Crosby and that behavior that makes it less of a transgression to consider oneself a fan, whereas Allen’s image is based largely on urban elitism, neuroses, and public scandal?

In the end, I decided that I can do both. Despite the internet baring fangs, I don’t consider my excitement for a Woody Allen movie starring Louis C.K. as a thumbs up for child abuse. If Woody Allen were put on trial tomorrow and found guilty, I would stand one hundred percent behind his being sentenced to the full extent of the law. But I refuse to let the court of public opinion tell me that I’m a monster for enjoying his films.

Many have backed up the idea that supporting Allen post-letter is particularly immoral due to his own close connection to his work, which he commonly writes, directs, and stars in. I find that interesting but also not convincing. That may make Allen and his work an easy target for boycotting, but does a human face make a cause more just? Making Allen representative of the larger issues facing survivors of sexual abuse may be very of the moment, but I think efforts should be focused on reforming the law and funding organizations working to help survivors rather than tearing down people who choose to keep their copy of “Midnight in Paris.”

Whether it’s doing things you know are bad for you or supporting industries you don’t believe in, our day to day lives are largely rooted in problematic behavior. Just as I choose to compartmentalize certain decisions, I choose to continue watching Woody Allen movies. It doesn’t make me a monster—it makes me human, with my own struggle when it comes to someone I’ve long admired standing accused of something I find abhorrent. It’s not for the internet to tell me whether or not it’s possible to reconcile the two; it’s for me to work through and understand on my own.

Share this:

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

This is a very well-balanced take on the issue. Well done!

Thanks!